KEANE'S DESIGNS: David Edgar

Photographs of John Keane tend to the unsmiling and intense. Some of his self-portraits - which include one of him naked, carrying a bloody heart - have the same feel. The son of a stockbroker, educated at Wellington, Keane has worked his way through what some would see as a predictable portfolio of left-liberal subjects and sites, from the Falklands to the rainforests, from Murdoch to the miners, from Northern Ireland via consumerism and urban angst to the war on terror. Like many leftist writers, Keane visited the Sandanista’s Nicaragua in the 1980s, and a later central American trip was organised by a group of ‘Artists for Guatemala’, which included Harold Pinter, Charlotte Cornwell and Julie Christie. Keane’s studies of urban desolation and blind corporate greed are angry calls to arms. Famously, his painting of a Mickey Mouse doll surrounded by turds on a Kuwait beach at the end of the 1991 Gulf War was excoriated in a Sun leader for smearing our brave boys. Superficially, he is one of the those artists whom Keats suspected of ‘having designs on us’.

The more you look at his work, however, the more surprising those designs are. One of them is to make us laugh. In Nicuaragua, Keane painted a picture of himself holding a toy gun and titled it Portrait of the Artist Pretending to Be a Cultural Guerrilla. As someone who produced a student revolutionary magazine called Guerrilla in the late 1960s, I have sympathy both with the pose and the deprecation.

As Mark Lawson points out in his monograph on Keane’s work, Keane has developed a peculiarly painterly method of layering his meanings: his subjects often consist of reportage (usually recorded by camera), but the authority of his observation is challenged by the use of collage (its materials collected on site), and the meaning twisted by ironical titles (sometimes bitter, sometimes playful: an early still life is titled I Could Do That). Keane also conveys meaning by framing his work (one of the Nicaragua pictures is surrounded by US banknotes) and, on occasions, through his description of materials: in his Amazonian series Saving the Bloody Planet, the works titled Souvenirs 1-6 are painted in ‘oil on illegal wood’. One further, unplanned layer of irony is provided by his works’ ultimate destination: Keane’s 1986 Futures, which shows a gang of desperate financial dealers, pushing each other aside in a gadarene rush for profit, is now owned by the Chase Manhattan Bank. If Keane has designs on us, they are conveyed by every aspect of his art; like the text, the context goes all the way down.

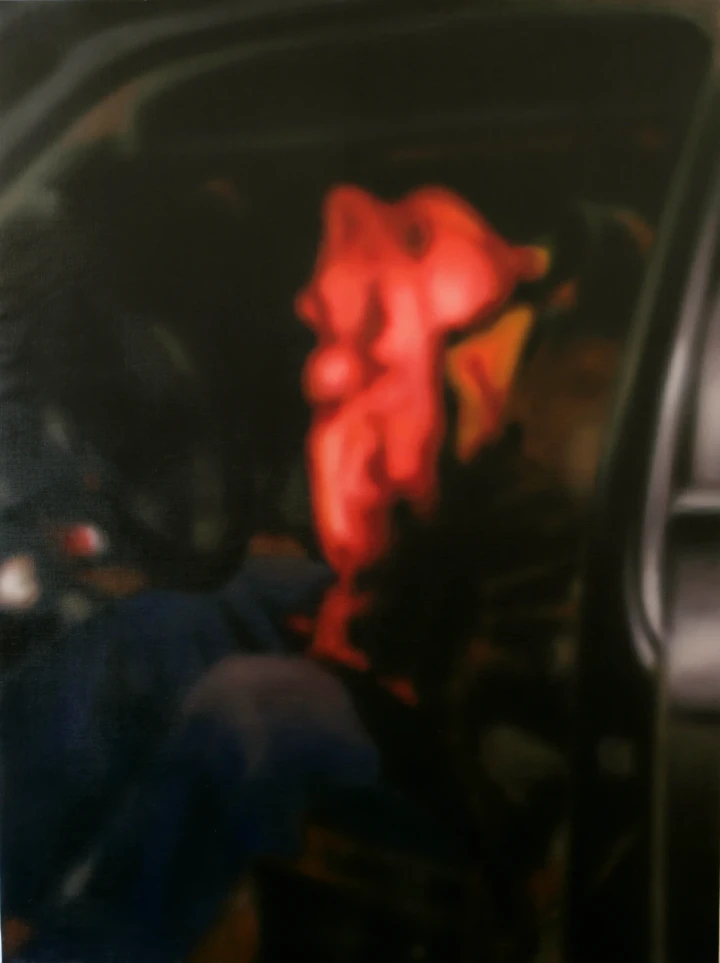

During his career, he has also developed a repertoire of favoured images, which gain additional resonance with each new appearance: from the red sports cars of the 80s paintings via the supermarket trolleys of the 90s to stencilled images of oil platforms, tanks, guns and disabled women in last year’s Angola exhibition. Most notably, Keane’s lush, thickly painted, sensual canvasses treat the bland, matt surfaces of contemporary life - computer screens, keyboards, mobile phones - with the richness and exuberance of human flesh.

Keane has left his early, swirly style behind (partly because he was fearful of becoming formulaic). In his 2006 exhibition Fifty-Seven Hours in the House of Culture, Keane manipulated stills from a television documentary on the seizure of over 800 hostages in a Moscow theatre by Chechen rebels in order to confront the emerging issue of Muslim terrorism. The same year, his New York exhibition Guantanamerica took iconic images of Muslim prisoners at Guantanamo Bay as raw material for a meditation on submission, dehumanisation and torture.

In this work, Keane is part of a movement towards documentary which echoes verbatim theatre, fact-based films and news-based novels like Gordon Burns’ Born Yesterday. Despite drawing their subject-matter from current politics, these strategies are often accused of evasion. The use of transcripts (of tribunals, interviews of news reports) releases the author from responsibility to express a view, implying that there may not be a coherent view to be expressed.

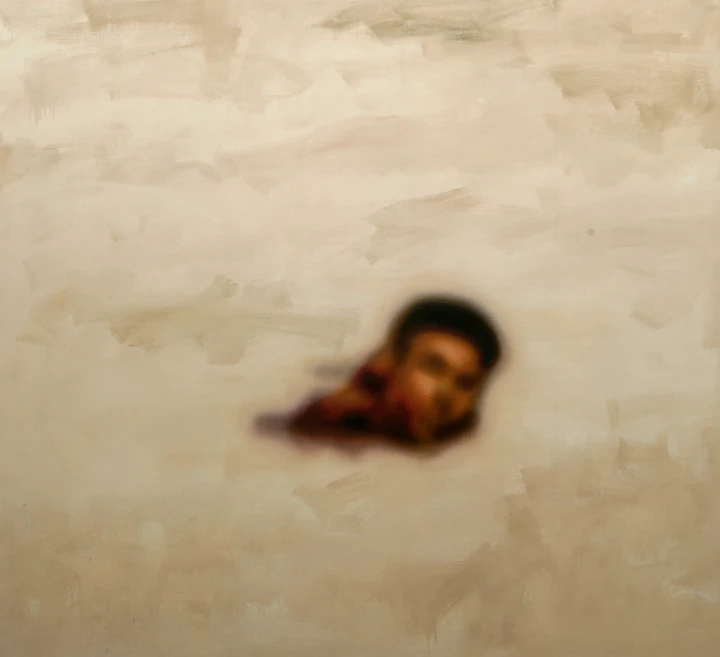

For me, however, Keane’s new work is less about sources than contingency. Like many contemporary novels and plays, Keane is increasingly crashing together seemingly disparate elements and inviting us to make connections between them. Like a serial composer, Keane spun infinite variations (in size, materials, technique and reference) on the images of the Chechen theatre siege. In Guantanamerica, the images became increasingly abstracted, so that what started out as a chained prisoner being led by a guard ended up as a shadow and a blob. But Intelligent Design is about variation and juxtaposition, within and between two dramatically distinct sections.

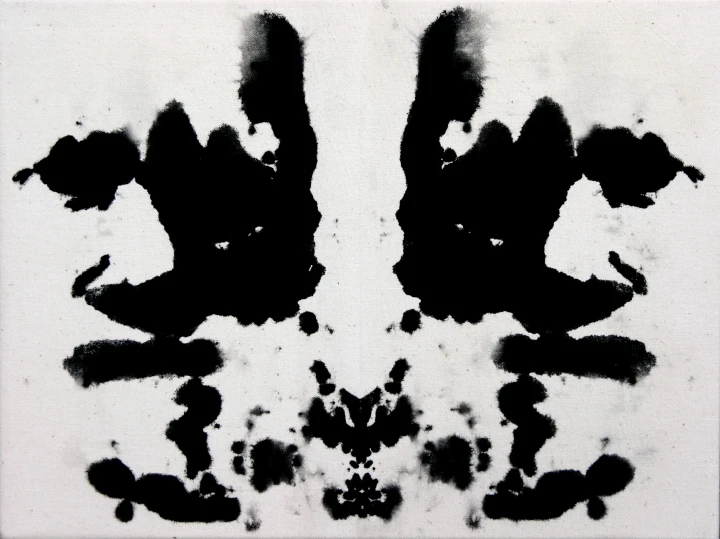

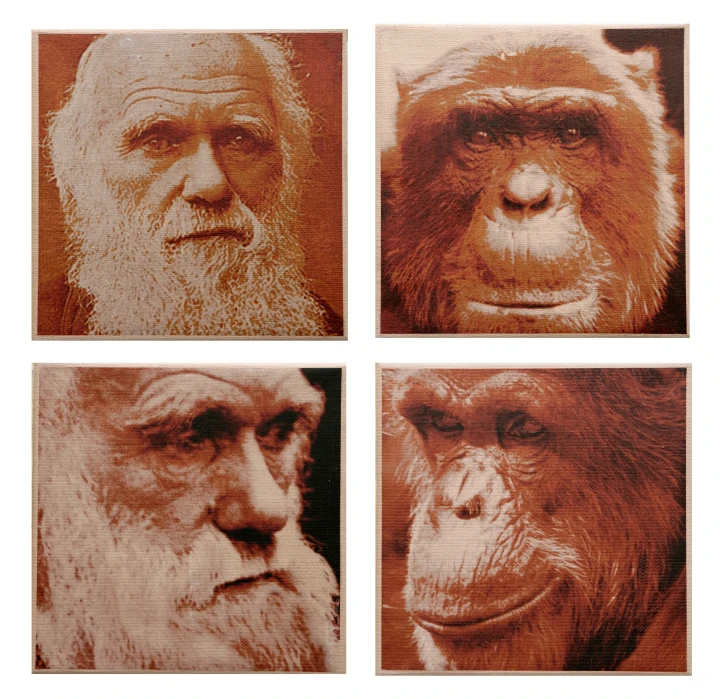

Half of the exhibition consists of a dazzling series of visual conjuring tricks, in which the seemingly abstract, repetitive symmetry of a Rorschach blot conceals bugs, breasts, beards and bears. Both the Rorschach and the butterfly pictures conceal the face of Charles Darwin, as does a Darwinianally significant peppered moth. The eyeball markings on Keane’s butterflies (some of which also conceal a stencil of Darwin’s face) raise a fascinating evolutionary question: we see the balls as eyes, but did predators, and, if so, did it put them off (the title of these paintings - the Predator’s Power of Appreciation - is from Nabokov)? How much are we hard-wired only to register the familiar? And, having registered, what is the line between the threatening, the fascinating and the beautiful?

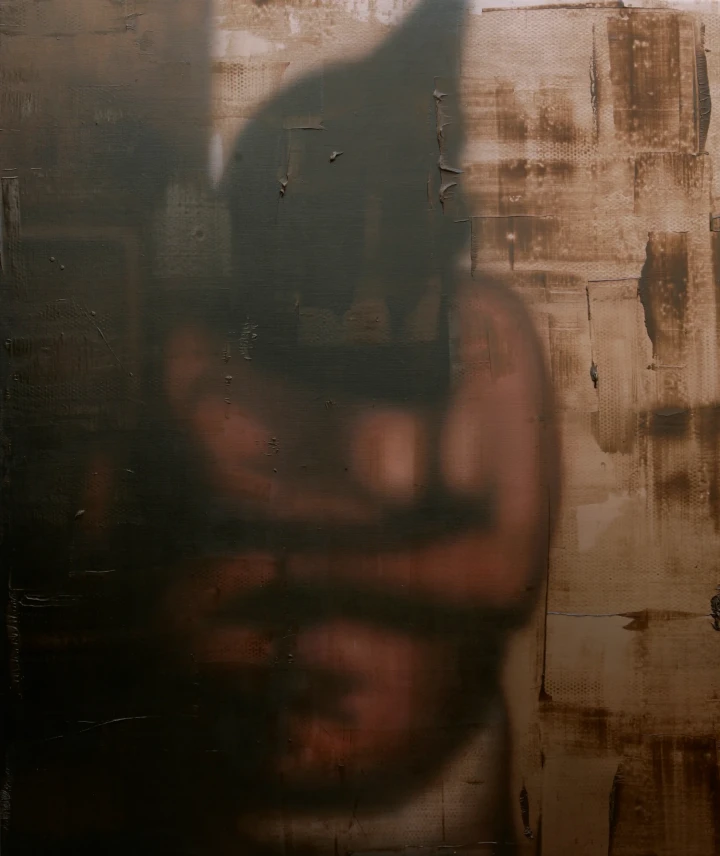

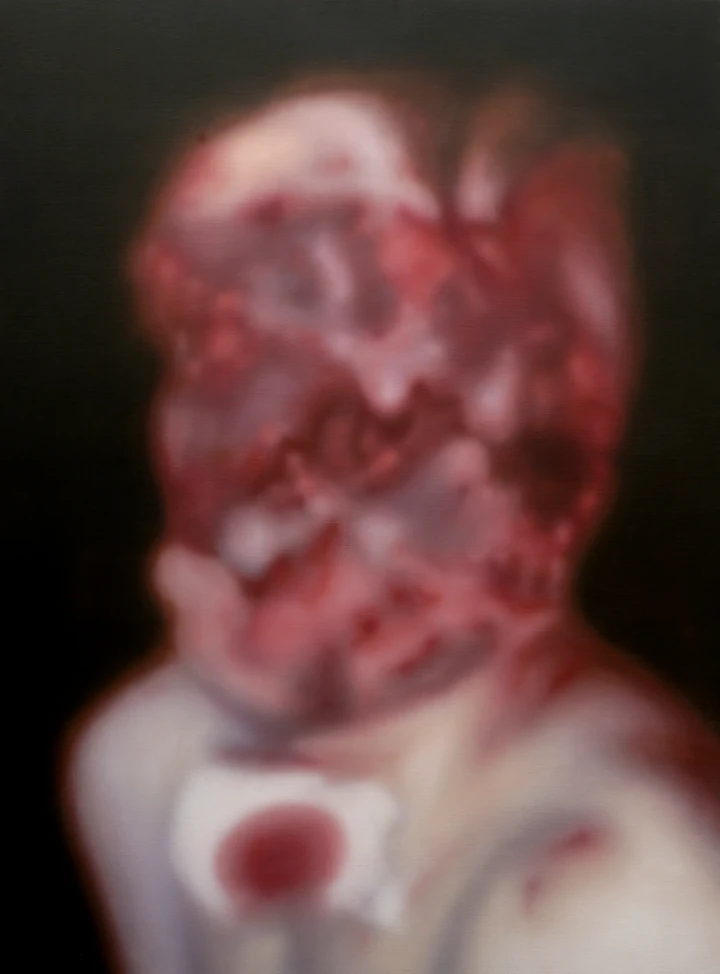

The Darwinian half of the exhibition thus playfully juxtaposes images within and between its constituent works. It appears to stand in stark contrast to the other section, a series of variations on noted, and often horrific, images from the war on terror in Iraq war and elsewhere. Because the paint surface is smoother and cooler than that of his earlier paintings, you could see it as a cooler treatment of its subject matter. In fact, the style is a response to the extremity of the material. Most naturalistically legible in Bag Dad and Bomb Head, necessarily blurred in Bag Head, Rag Head and Jar Head, some of Keane’s images are instantly recognisable, others take time to decode. In Dog Bag, an abstracted image of a hooded and submissive prisoner - the orange curl of his body grimly echoing the Adidas tick - faces a huge, threatening dog.

In Division of Cells, this image is further abstracted, reduced, quadrupled, mirrored, and morphed into a Rorschach image. The title of the painting (punning biological and terrorist cells) adds a verbal link to the visual connection. Division of Cells is clearly the hinge of the exhibition, but it is also a bridge. In truth, the exhibition is so much a game of two halves, as a journey along a spectrum. Easiest within an individual painting, finding the connection between Keane’s images leads the viewer, if not to the meaning, then to identifying the journey which he is inviting him or her to take.

One juxtaposition, clearly, is between reason and terror. For Keane, Darwinism stands for a spirit of rational, free inquiry which fundamentalism rejects. The title of a wittily symmetrical doubling of photographs of Darwin and a contemplative ape (The Sons of Adam and the Sons of Monkeys) is a quotation not from an American creationist but a Chechen warlord. Internal Combustion is an abstraction of the car driven by would-be suicide bombers at Glasgow airport, the day after a car-bomb attack on a west end nightclub was foiled (John Keane retails attractively-priced posters and T-shirts of three miniskirted young women set in a rifle-sight, titled Slags Against Jihad). The title of a picture of 7/7 bomber Mohammed Siddique Khan cradling his pixillated child is Love You to Bits, a title with all the bitter irony of Keane’s earlier attacks on consumer capitalism. As The Sun condemned Mickey Mouse at the Front, the Imperial War Museum refused to exhibit a painting framed by pages from a copy of the Qur’an abandoned on the Basra road.

The only picture in the exhibition approaching Keane’s old, realistic style is of the body of the murdered anti-Muslim filmmaker Theo van Gogh. Yet, as in his earlier Gaza pictures, the author of this exhibition remains passionately opposed to the torture and brutality justified by the war on terror. I think Keane is inviting us to explore not just connections but contradictions. One of the striking features of its two parts is that one is unnaturally still (chained prisoners, severed heads, dead bodies) while the other is unnaturally mobile (as images of Charles Darwin leap with dizzying speed in and out of the punning Four Bears, I Think and Darwinius Prodigiosus). What both sets demand of us is to look at the paintings and to think about their source material, their treatment, and their relationships with each other. Notably, Division of Cells points both literally and metaphorically in both directions, inviting us to question what is cause and what is effect. It poses a challenge both to the liberal hawk belligerati who think that terror justifies a dismantling of our rights and liberties, and those (like me) who instinctively support a beleaguered and demonised minority, but hope that its future lies with an open democratic Islam - the Islam of solidarity and social justice - rather than Wahhabism and Jihad.

The invitation to question is rendered clearly in a final painting, stylistically distinct from everything else in the exhibition (and John Keane’s work). In a conscious evocation of the iconic 1950s Start Rite advertisement, Star Dust shows two children (in fact, Keane’s own), holding hands and gazing at the stars. Like the exhibition as a whole, this painting is an invitation to interrogate our universe and its design, as well as our designs upon it.